.svg)

.avif)

A lot of you probably read the title to this post and said, “Isn’t it true that happy people are more likely to get married in the first place?”

Certainly, there is truth to that statement. Unhappy people are less likely to put themselves out there, attract a partner, and see a relationship through to marriage and beyond. Married people tend to be more social, healthier, better educated, and have more engaging jobs - all factors that increase happiness and life satisfaction regardless of marital status.

But, controlling for pre-marital happiness and other confounding factors, marriage itself is shown to have a positive effect on perceived wellbeing.

How positive?

There are two contending views in the literature about marriage’s influence on happiness. The first position holds that marriage provides a brief boost to self-perceived life satisfaction that dissipates after only a couple years, at which point married people return to a satisfaction baseline equivalent to where they would be had they remained single. This conclusion is reached by measuring people’s reported happiness 1-2 years before and several years after marriage.

This view is incorrect.

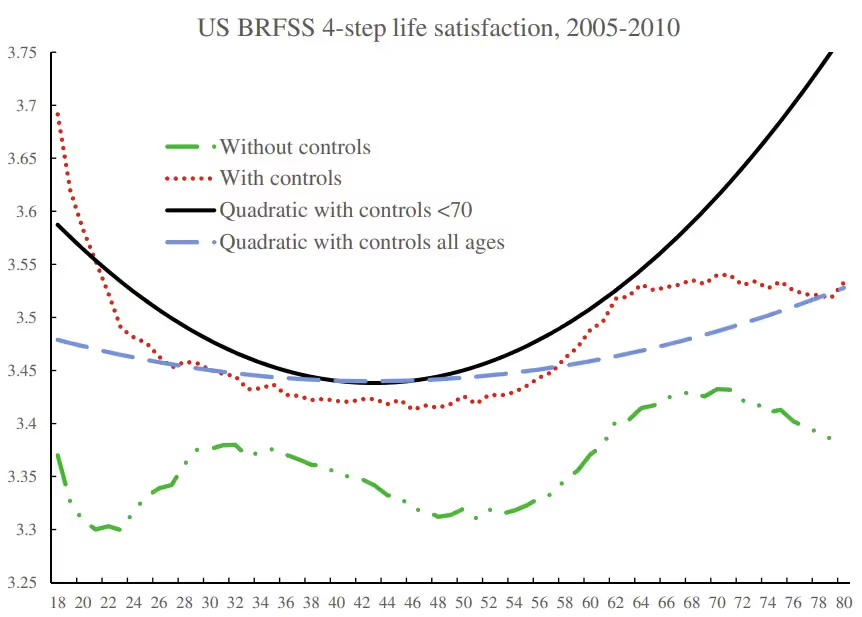

First, the few studies backing the “return-to-baseline” hypothesis fail to account for how happiness naturally fluctuates with age. This is important, because your happiness baseline is not constant throughout life. Instead, it follows a ‘U-shaped’ curve. People tend to experience a decline in life satisfaction starting in their mid-20s that persists through their 40s until bottoming out around 50, when reported wellbeing begins to rise again.

The explanation for this curve is simple, and unless you’re very young, you probably know what I’m talking about already. Aging is a stressful experience, and 25-55 are your grind years. Since most marriages happen between ages 25 and 40, newlyweds’ self-reported life satisfaction should be expected to decline for some number of years after tying the knot. The salient happiness reference point for a married person is not how they felt when they were younger, because growing up changes your life in too many ways to count.

To measure marriage’s effect on happiness, we have to compare married people to single people at the same point in their lives.

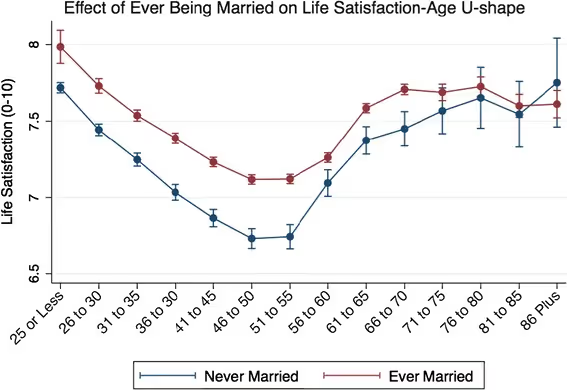

Married and unmarried people both experience the ‘U-shaped’ happiness curve through middle age, but for married people, the U is shallower and happiness is greater across time than for their single counterparts. Accounting for aging’s downward pull on life satisfaction, what looks like a “return to baseline happiness” for one person is still an improvement over how they would rate their lives at the same point in time had they remained single.

A second problem with the “return to baseline” hypothesis is the timing with which these studies record individuals’ self-reported satisfaction.

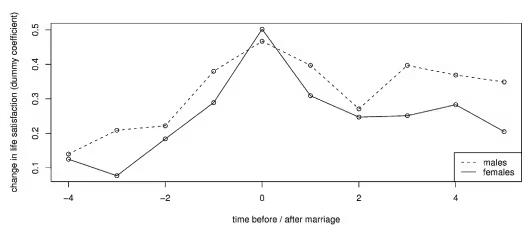

Longitudinal studies arguing that marriage grants only a temporary boost to happiness measure baseline happiness 1-2 years prior to marriage. But 1-2 years prior to marriage, it’s quite likely you’re already enjoying the benefits of a committed relationship with your future spouse. When researchers ask for a sample baseline 5 years prior to marriage, the happiness benefit of marriage looks much larger.

So, when they say marriage itself has a muted effect on happiness before returning to baseline, it’s important to note that “baseline” means “quasi-married person in a committed relationship leading to marriage,” not “lonely single individual.”

As you can see in the second chart above, the most substantial gap in happiness between the married and unmarried (controlling for other influencing factors) is observed between ages 40 and 55. The social support of a spouse significantly eases the stressors of middle age with the type of longstanding companionship only a husband or wife can provide. The lines converge later in life as widowers and divorcees become more heavily weighted in the sample (because the study measures ‘ever married’ as opposed to ‘currently married’). It’s fair to assume that for the portion of the ‘ever married’ category that remain married, the satisfaction advantage over the ‘never married’ cohort is larger.

(It’s also likely that satisfaction within the ‘never married’ category is buoyed by people with lifelong companions they never marry, though I suspect this effect is relatively inconsequential).

Two remaining factors to consider are friendship and compatibility.

It has been shown that marriage and number of strong friendships are two of the most significant independent correlates with life satisfaction. As it turns out, the incremental gain in happiness of having one more friend is significantly smaller for the married than the unmarried, because a spouse provides most of the support and companionship a single person has to rely on friends for.

With respect to compatibility, 53% of men and 43% of women report that their spouse is their best friend, and these people experience almost twice as much additional life satisfaction from marriage as others.

The takeaway is this: If you want to maximize your odds at a happy life, find someone you love, marry them, and take care of each other forever.